The anatomy of growth

A few weeks ago, a woman in park was asking me: how old is your dog? I answered tongue-in-cheek “35 years.” The dubious woman said laughing “he does not look that old!” Of course, I was talking in human being years. Our dog is a lovely Havanese who is 5 years old.

What about the age of a company? For a long time, I have multiplied by 3 the age of a company and it works pretty well. It typically takes somewhere around 7 years for a startup to be acquired or go public. That’s like being 21 years old. Going public at that age is like being legally able to drink alcohol. If you drink too much and don’t follow the rules, you pay a high price. Same for a company that misses its quarter estimate after going public.

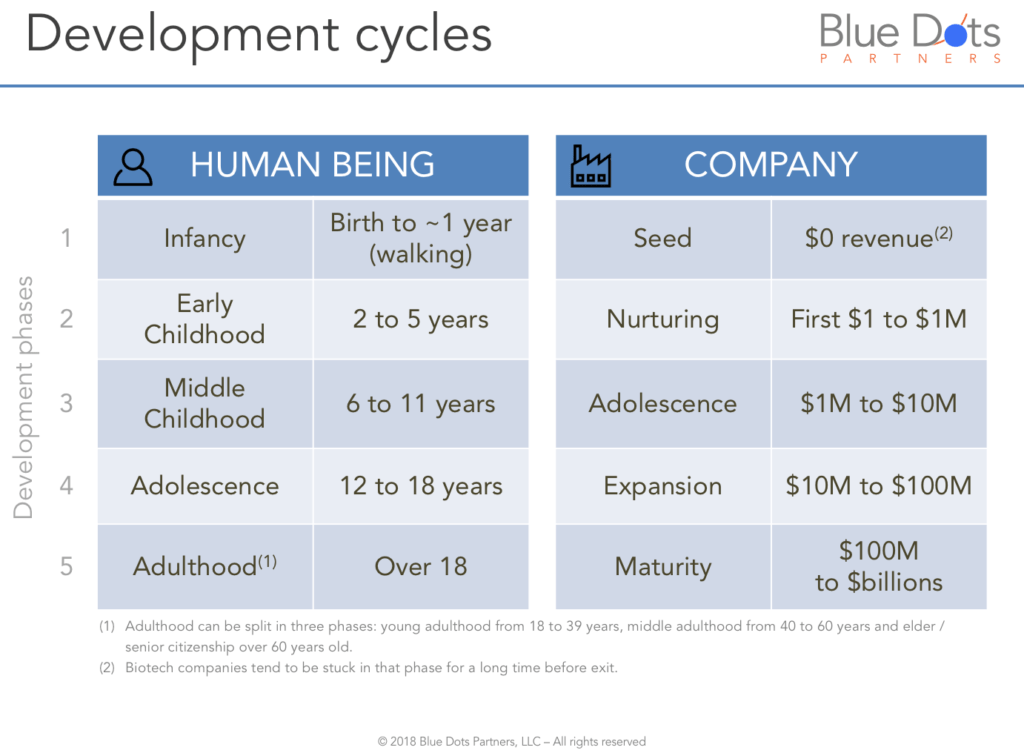

Human beings go from birth to end of life through different phases of growth. It is well established that there are five phases of growth for people:

- Phase 1: Infancy (birth to about one years old – ability to walk)

- Phase 2: Early childhood (one to six years)

- Phase 3: Middle childhood, also known as prepubescence (six to 12 years)

- Phase 4: Adolescence (12 to 18 years old)

- Phase 5: Adulthood (over 18 years old, with young adulthood from 18 to 39 years, middle adulthood from 40 to 60 years and elder / senior citizenship over 60 years old)

In a similar way, companies also go through five different phases of growth throughout the business lifecycle:

- Phase 1: The company is at a concept and development phase of the product: no revenue is generated.

- Phase 2: Nurturing (or “Startup phase”): First sales to whomever is willing to buy, i.e. “first customers”. Revenue is just starting and usually driven by the founders or CEO. The goal is to see if the market responds and to keep going and “live another month”. This is all about proving the right to exist.

- Phase 3: Adolescence where revenue starts to grow in a more predictable way and cash flow improves. This is where processes are defined, skilled employees are hired, and a support infrastructure for sales, marketing, and customer care is in place. This is more around the survival stage and “living another year”. The owner or CEO continues to be synonymous with the business at that stage. It’s fusional: he / she “is” the business.

- Phase 4: Expansion: At that stage, running the business is now a well-understood mechanism and the flywheel is turning with a decent level of predictability. This is the venturing phase into unknown territories, such as: geographic expansion, new product lines, establishment of distribution and channel partners, first acquisition, upgraded Board of Directors. This is the phase of rapid growth, where the owner, founder or CEO may not be the best person to drive that expansion anymore. VCs often consider bringing an “adult” CEO and an experienced CFO during that phase and have the founders focus on what they were best at during the early stage of the company (could be product development, marketing or sales). Attention is focused more on the future of the business rather than its current condition.

- Phase 5: Maturity and exit. Profits and cash flow generation are now a well-oiled machine. Growth rates typically slow down at this phase. Controls, strategic and operations planning, and processes have to be in place to be successful during that phase of the business. Systems (finance, HR, IT, CRM, client success, ticketing for support, product development) are now well-established in a “must-use” manner. Executives now undertand and apply operational and strategic planning in a decentralized organization. Delegation is not an after-thought, but a must-have. Now size, financial well-being and management talent can be leveraged for a great exit or a “take no prisoners” acquisitive approach. This is a dangerous phase where innovation and entrepreneurship can easily get squashed and politics is in high gear.

One of the major differences between human beings and companies is end of life. While human beings typically die from all kinds of unexpected circumstances, according to a Startup Genome Report, an estimated 90% of startups end up with self-destruction. In other words, it was the doing of their own founders, not so much things that are out of their control, such as market conditions that led to the demise of the company. It’s often said that, in the end, it is the lack of cash that kills the company, meaning only one of three things: the company spent too much, and/or not enough revenue (at a high enough gross margins) was generated, or the CEO was not able to secure additional funding. This is why companies, even at a relatively small level of revenue, can live for dozens of years as long as they are cash flow positive and generate enough oxygen to breathe over long a period of time.

While lack of cash certainly causes pain and eventually death for a company, the real cause, I would argue is not lack of cash. It’s lack of revenue growth. There is no shortage of capital, especially in today’s market, where investors would not be willing to invest in a company that is growing faster than the market it which it operates. Lack of top-line growth is really what should be written on the company’s death certificate, not cash depravation. This is akin to writing “the person stopped breathing” on a death certificate instead of “extensive internal bleeding due to a large trauma caused by car accident.”

I would hesitate to map the five phases of company growth to a revenue number, but it might look something like this:

In the end, the right to exist can be solidly secured by top-line acceleration. Growing faster than the market is the only option to generate sustainable shareholder value creation.